How Should the Story of Inception End?

By

Jau-lan Guo

(拉下面有中文版本)

Widely known as one of the first-generation contemporary artists of Taiwan's post-Martial Law era, Yang Mao-Lin, a key member of the Hantoo Art Group, serves as an ideal example of how an artist has committed himself to socially-engaged art practice. His body of works brings forth questions as to how individual subjects may respond to or engage in collective consciousness: does one simply insert oneself smoothly into social processes in hopes of driving the society forward? Or does one concentrate on the inner awareness as a means of avoiding or even defying the immediate crisis? Or perhaps, as one seeks to make sense of the external world, the “evil powers-that-be” that the individuals have been fighting are swiftly and quietly evolving from the mighty inflictor of perceivable social-political injustice to the ever-proliferating commodity culture? Under these circumstances, one may begin to think, perhaps digging into one's own consciousness, albeit seemingly passive or even reclusive, may in fact be a more effective way of engaging with the increasingly complex and dynamic social reality.

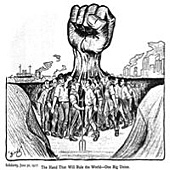

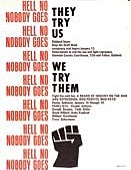

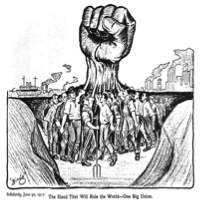

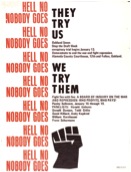

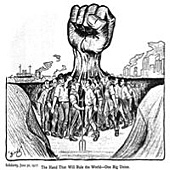

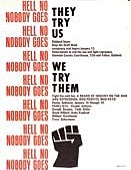

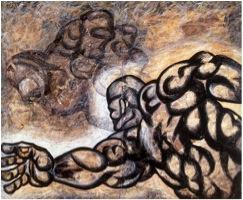

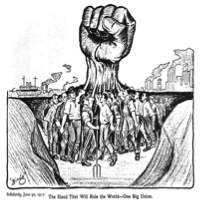

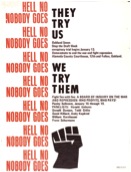

Yang Mao-Lin first made his name in Taiwan's contemporary art scene in the 1980s with his two pieces – The Truth (Plate 1) and the Made in Taiwan series. This period is marked by an explosion of debates over the island's national identity and “Taiwanese subjectivity”. Whereas the Made in Taiwan series makes a stance against the national collective memory by juxtaposing a number of powerful historical symbols, The Truth, which appears to blow a raised fist at the viewers, may instantly evoke impressions of some left-wing or feminist activist posters, such as the Taller de Grafica Popular of Mexico (Plate 2) and the Stop Draft Week (Fig.) of the anti-Vietnam War protest movement in 1968. All these images strike the audience with the depth of focus and power of the message.

Plate 1

Plate 2

Plate 3

In the wake of democratization and localization movement in Taiwan's post-Martial Law era, Yang Mao-Lin and his contemporaries embarked on a quest to explore their relationship with Taiwanese art history, and at the same time to discover and develop Taiwanese identity through visual art with the support and endorsement of a newly emerging art scene shaped largely by the combination of the art market and the museum/gallery system.

An artist may appear alone and fragile when facing up against the immovable wall of authority, but the striking contrast may inadvertently help to enhance the image of the artist as a hard-edged hero forever poised to throw a fist punch at the mighty authority. Yang Mao-Lin's earlier works may indeed be characterized by a strong militant political tendency. However, as the new millennium approached, the artist seemed to take a more personal, lyrical turn, opting for a more flexible aesthetic approach as he moved away from the confrontational tone in favour of a subtler, or even cunning, aesthetic strategy. His post-millennium works, such as The Sword-holding Great Devil Vidyaraja (Plate 4) and Astro Bodhisattva (Plate 5) can be seen to exemplify how Yang Mao-Lin focusses on the symbolic framing of his dissenting vision in attempts to stretch cultural boundaries, and the works exhibited in Temple of Sublime Beauty: Made in Taiwan, which represented the Taiwan Pavilion in the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009 the summit of this creative endeavour. Invited by German curator Dott Felix Schoeber, Yang’s sculptures of Eastern hybrid deities (Plate 6), A Story About Affection – Extraordinary Love Vajradhara (Plate 7), A Story About Affection – Beloved Mermaid Vajradhara (Plate 8) and A Story About Affection – Beloved King Kong Vajradhara (Plate 9), invaded the Saint Giovanni e Paolo Church, the oldest and holiest Catholic church in the city, with their noisy manifestations of religious-cultural hybridity.

Plate 4

Plate 5

Plate 6

Plate 7

Plate 8

Plate 9

Surprisingly, dismissive reactions of the religious establishment against this curatorial arrangement and subsequent confrontation between art and religious faith, East and West, sacred and profane, did not happen as it had been expected. According to curator Dott Felix Schoeber, the local Catholic clergy simply regarded Yang's sculptures of Mazinger Z or Peter Pan as interesting works of art which would pose no threats whatsoever to their faith in God: “What Jesus Christ has been through was far worse than simple expressions of dissent. He was crucified on the cross; a few wooden statues will not make him fall off the cross again.”

It was, ironically, the servants of the secular public administration who cried desecration when presented with the curatorial proposal of Yang Mao-Lin's exhibition. The Venice municipal agency in charge of preserving cultural heritage reacted with disapproval, stating categorically that the achievement and cultural-historical status of the Renaissance is beyond the reach of any living artist. It was therefore decided that there would be no mimicry of any statues near Scuola Grande di San Marco or any of the marble statues of the saints on top of the church roof of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. It seems that instead of breaking down a whole system of signifiers and codes, Yang Mao-Lin's latest works, by putting together various different kinds of realities, simply softened the rigidity of the system as they infiltrate the subconscious of the public and alter its ideological contents. Such an artistic tactic may appear subtler, but by no means is it any less effective or less fascinating than attacking the system from the outside.

Inception: the Inward Ecstasy of Expanded Consciousness

As discussed in previous paragraphs, Yang Mao-Lin's artistic style has undergone a major shift in the last decade from a confrontational to a more cunning, debilitating approach. This change calls for comparison with the Hollywood blockbuster movie Inception (2010), in which the main character Dom Cobb enters, and plants life-changing ideas in, the dreams of his targets as he also tries to heal his own mental wound. The act of infiltrating one's dream may be a gentle one; the subversive power lies in the idea itself. As Cobb in Inception puts it, “An idea in your subconscious can rewrite all your rules of living.”

On the other hand, however, while on of the most captivating object seen in the film Inception is a spinning top which Cobb uses to distinguish between reality and dream, Yang Mao-Lin does not appear to offer a marker of boundaries of this sort in his works. As far as the artworks are concerned, if there is such a thing which marks the inside from the outside, or dream from the reality, it would probably be the “white cute” i.e. the mechanism of art exhibitions. Once inside of the white cute, one can just do as one wishes.

Sometimes it is hard to reach a satisfactory conclusion as to what has driven an artist to change his direction – social-cultural factors, inner impulse, or personal growth. In the case of Yang Mao-Lin, all that we know is that he has, in the past, confronted and challenged the institutional system of power with strong-impacting images, but is now choosing to shift the boundaries of reality through creative visualization which promises an ecstasy of expanded consciousness.

Perhaps one can ask this question: does a slippery consciousness not stand as the dualistic opposite of the hard, solid, homogenous stance of subjectivity? If that is indeed that case, it can be suggested that Yang Mao-Lin's “melting pot” serves as artistic representations of liquid subjectivity which, habitually associated with the qualities of fluidity and mobility, pass around solid obstacles and dissolve the solid mass with lightness.

Yang Mao-Lin's works have indeed accommodated different cultural and symbolic systems: the East and the West, the sacred and the profane, art and religion, the local and the global. More importantly, Yang's “melting pot” of these cultural-symbolic systems, which effectively erode the rigid boundaries which have once shaped our understanding of the universe, can be seen to illustrate the spirit of “liquid modernity” – a term which sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has coined to describe the present condition of the world as contrasted with the "solid" modernity that preceded it. According to Bauman, the passage from "solid" to "liquid" modernity has created a new and unprecedented setting for individual life pursuits, confronting individuals with a series of challenges never before encountered. Social forms and institutions no longer have enough time to solidify. In our time of liquid modernity marked by a redistribution and reallocation of modernity's 'melting powers', “interpreters and brokers [are] taking over most of the task previously reserved to the legislators”,1 and “life-politics” takes over public politics, critical theorists are having to adjust their role to become interpreters between different systems of perception in a bid to assist and promote autonomous communication between cooperating agents.

As Bauman describes, “From the meeting with solids they [liquids] emerge unscathed, while the solids they have met, if they stay solid, are changed – get moist or drenched.”2 Bauman's conceptualization of “liquid modernity” leads one to contemplate if the attacking force, the the clenched fist which was once aimed at the solid rock of political authority, will remain a rock solid, homogenous entity after all.

One may go on to ask further questions: is the solid still existent? If it is, then in what form does it exist in our current society? How does Yang Mao-Lin return to reality, once he has initiated into a full-blown fantasy and entered a different realm of reality?

For modern subjectivities, to evolve from solids to liquids is to strategically avoid direct confrontation and overt conflict with the rigidity of the inflexible, collectively-oriented order. It also allows for sufficient fluidity and dispersibility to infiltrate across the furrow boundaries of the system to plague it with endless waves of ecstasy. To conclude, I would like to quote Cobb from Inception again to help understand the fluid and mobile nature of “liquid subjectivity”: “You never remember the beginning of your dreams, do you? You just turn up in the middle of what's going on.”

全面啟動之後

郭昭蘭

作為台灣解嚴以來第一代藝術家,悍圖社成員楊茂林的藝術歷程與這個島上所經歷的一切,已經提供足夠的時間寬幅,讓人重新去想像這條綿密而轉折的軌跡;個體如何對應於更大的集體,是把自己平行的置入作為推進力量,抑或是轉身向更為個人想像的浸潤,以腫脹的精神意識迴避所謂集體迫切的危機?或者,那個被拿來對應於自我的集體,從社會政治轉向了文化商品角色的投射。後者顯得避世,但是否實則進入某種更加難以捉摸的社會情境?

1980年代,楊茂林的「真理」(圖一),「肢體記號篇」等作品將他推向台灣當代藝術的舞台;飽滿的拳頭,向著觀眾的方向出擊。「Made in Taiwan」系列並置歷史性符號, 向著集體的主體意識發出他的言論;而那同時也是台灣社會所謂主體意識討論最為迸發的時期。那隻出擊的拳頭,令人聯想到墨西哥海報(圖一),1968年的新左派停止徵兵運動(Stop Draft week)(圖二),以及許多學生運動,女性運動的圖騰。激進的抗爭是他們共同的態度,立場鮮明,態度堅定。

圖一

圖二

圖三

就這樣楊茂林與他同時代的藝術家,建立了台灣藝術史屬於當代的最初始軌跡與實踐,他們對台灣性(Taiwanese)本身的主觀關注,呼應了解嚴後台灣社會集體熱切的情緒; 終於,在長久的遙想他鄉之後,藝術的語彙向著這個島上發出了他們的聲音;作為藝術家必要的使命感,建立了他們與這個逐漸開展的藝術史之間的初始關係。隨著藝術體制的逐漸建立,屬於市場機制與美術館機構的力量與他們背靠著背地,相互支持構建這個島上逐漸成型的藝術歷程。

站在拳頭對立面的那個東西如果是硬版一塊,藝術家的身軀則相對單薄,但也因此確立了藝術家相對陽剛而英雄化的姿態:對於迎面而來的龐大集體,用拳頭去對應。從作品處理的意識來說,經歷解嚴世代對現實衝撞與對抗的姿態,楊茂林在世紀末進入21世紀之後的系列如「持劍的大魔明王」(圖四),「原子小菩薩 」(圖五),中被框架出來的界限則比較像是符號文化平台上的,他像是投身想像幻境的肉身,硬漢拳頭被一個越來越膨脹的滑溜精神體所取代,輕快矯健地在他的意識幻境中滑行,彈跳,跨欄,飛衝 ,彷彿對立的姿態被拉高成純然感性的張力。只怕不夠噴張,張力不夠飽滿,不夠腫脹。於是藝術家身段更為柔軟,也更為狡猾的戳揉於文化上可能的疆界。我認為這高潮正是2009年威尼斯雙年展中的「婆娑之廟─ 台灣製造」。矗立在威尼斯最古老教堂SS Giovanni e Paolo的「東方神起」(圖六)。「無敵愛金剛」(圖七)中無敵鐵金剛與女金剛為所欲為的合體 ,變種的動漫角色「人魚愛金剛」(圖八),「金剛愛金剛」(圖九)等頭上發出了神像該有的光環之後,一一登上了莊嚴的天主教的聖殿。

圖四

圖五

圖六

圖七

圖八

圖九

在聰明的策展人巧妙的安排之下,這些「東方神起」進入了西方天主教的聖殿,開始想像中應該要發生拳頭般的對峙。然而,根據策展人的敘述,這想像中保守教會的反彈事實上並沒有發生,因為「對當地的修女、僧侶和教士來說,楊茂林版本的無敵鐵金剛和彼得潘只不過就是非常有趣的藝術作品:安其羅神父的回應是,區區的木製雕像並不足以動搖堅定的宗教信仰,他說『耶穌什麼大風大浪沒見過,不會因為這種小事就從十字架上跌下來。』反倒是世俗市府,「當我把楊茂林計畫書的原稿程交給威尼斯歷史遺產行政單位時,大喊“褻瀆神聖”的並不是教會,而是世俗政府:他們的反應是,義大利文藝復興是神聖的。一個還活著的藝術家搆不上如此崇高的地位,更不得凌駕其上;因此,不准有雕像模仿附近聖馬可會堂(S. Marco)和歌德式的聖約翰與聖保羅教堂(SS. Giovanni e Paolo)屋頂尖塔上的大理石聖像」似乎,圍繞在楊茂林作品周圍的,重點與其說是它解開了什麼象徵系統,還不是說是怎樣膨脹的精神意識滑溜地搓揉了堅硬的系統,將現實以怎樣的姿態加以合併。所以讓作品外引的系統的搖撼與它內部象徵系統的摧毀,同樣迷人。

腫脹的精神 意識的狂喜 全面啓動

從硬漢意識到柔軟滑溜的精神體,與作品並進的作者意識在此顯得如此的不同。 這讓我想到2010年好萊塢電影「全面啓動」(Inception)中主角柯柏如何藉著侵入他人的夢境,植入足以改變現實的意念,進而處理自身的精神創傷。侵入夢境看似一個無須動武揮拳的溫和行動,但有趣之處就在於心靈想像的本身,只要你敢想,要多囂張就有多囂張,要多顛覆就有多顛覆。就像電影裡所說的「一個單純的意念可以改變世界, 並重寫所有的規則。 」但是「全面啓動」中有一顆旋轉的陀螺,總是用來作為提示區別現實與幻境的索引; 只是,在楊茂林作品內部,並不存在這樣的旋轉陀螺。如果有的話,那就是作品外部那個白色方塊(white cube)所指射的藝術機制。進入這個白色方盒子,你可以隨心所欲。

有時我們難以追問藝術家姿態的轉變究竟來自外在社會的,個人內在衝動的,抑或是創作生命的開展,總總分析總是無法串聯出一條令人滿意的說法。但我們知到這是一位曾經對應現實,如今卻選擇在作品中自現實轉身,以深入幻象之境,膨脹其幻想狀態的藝術家。我們知道,在這裡我們即將經歷意識全面的登鋒狂喜,一個被藝術家全面啓動的「優雅的精神惡搞行動」。

或許可以這樣問的是,是什麼東西站在滑溜精神體的對面。是否正是那像拳頭一樣堅硬的主體意識。一個被想像成無可分裂而完整而堅固的主體意識。那麼從楊茂林的優雅的精神惡搞行動中我們經歷的就是如液體一般流動,消毀沿途堅固一切的液化了的主體,流動輕盈而具延展性的主體。

在作品的表面,楊茂林捲入了各種差異的象徵系統: 東西方動漫系統的與宗教意識的、世俗的與宗教的、美術殿堂與宗教殿堂的、在地宗教與全球文化商品的種種疆界;在此同時,他在作品的後面同時演繹了液化主體之樣態,這正好與包曼(Zygmunt Bauman)所說的液化的現代性有著互相說明的意味。包曼認為生產機制與權利運作方式的轉變,使得固態現代性中那種由以立法者之姿態發言的知識份子,在全球化的時代正被詮釋者這種角色所取代。他們是周遊於各種系統的詮釋者,協助轉譯,促進自主性的參與溝通。

包曼曾經比喻當固態遇上了液態的時候,液態不會受損,而固體卻容易遭受溶解、侵蝕、甚至滲透。如果這樣的對照是可行的話,我們能否從這裡回望當初當初拳頭指向的方向,是否仍然鐵板一塊呢?

鐵板還在嗎?鐵板現在又以怎樣的方式存在呢?楊茂林的幻境全面啓動之後,是以怎樣微妙的形式回到現實? 最後我想用「全面啓動」電影中的一句話,「我們不必知道夢是怎樣開始的,我們總是從中間進入 !」來說明這種液態主體意識的機動流質性。也許是為了順應更加難以捉摸的現實系統,個體化身為更具彈性的流質器官,以保障自身免於在硬碰硬的層層關卡中,粉身或碎骨。液態同時保證提供足夠的擴散張力,去滲透進入每一個堅固的系統,飽滿而囂張的將他的狂喜覆蓋在無所不在的堅固殘餘。

By

Jau-lan Guo

(拉下面有中文版本)

Widely known as one of the first-generation contemporary artists of Taiwan's post-Martial Law era, Yang Mao-Lin, a key member of the Hantoo Art Group, serves as an ideal example of how an artist has committed himself to socially-engaged art practice. His body of works brings forth questions as to how individual subjects may respond to or engage in collective consciousness: does one simply insert oneself smoothly into social processes in hopes of driving the society forward? Or does one concentrate on the inner awareness as a means of avoiding or even defying the immediate crisis? Or perhaps, as one seeks to make sense of the external world, the “evil powers-that-be” that the individuals have been fighting are swiftly and quietly evolving from the mighty inflictor of perceivable social-political injustice to the ever-proliferating commodity culture? Under these circumstances, one may begin to think, perhaps digging into one's own consciousness, albeit seemingly passive or even reclusive, may in fact be a more effective way of engaging with the increasingly complex and dynamic social reality.

Yang Mao-Lin first made his name in Taiwan's contemporary art scene in the 1980s with his two pieces – The Truth (Plate 1) and the Made in Taiwan series. This period is marked by an explosion of debates over the island's national identity and “Taiwanese subjectivity”. Whereas the Made in Taiwan series makes a stance against the national collective memory by juxtaposing a number of powerful historical symbols, The Truth, which appears to blow a raised fist at the viewers, may instantly evoke impressions of some left-wing or feminist activist posters, such as the Taller de Grafica Popular of Mexico (Plate 2) and the Stop Draft Week (Fig.) of the anti-Vietnam War protest movement in 1968. All these images strike the audience with the depth of focus and power of the message.

Plate 1

Plate 2

Plate 3

In the wake of democratization and localization movement in Taiwan's post-Martial Law era, Yang Mao-Lin and his contemporaries embarked on a quest to explore their relationship with Taiwanese art history, and at the same time to discover and develop Taiwanese identity through visual art with the support and endorsement of a newly emerging art scene shaped largely by the combination of the art market and the museum/gallery system.

An artist may appear alone and fragile when facing up against the immovable wall of authority, but the striking contrast may inadvertently help to enhance the image of the artist as a hard-edged hero forever poised to throw a fist punch at the mighty authority. Yang Mao-Lin's earlier works may indeed be characterized by a strong militant political tendency. However, as the new millennium approached, the artist seemed to take a more personal, lyrical turn, opting for a more flexible aesthetic approach as he moved away from the confrontational tone in favour of a subtler, or even cunning, aesthetic strategy. His post-millennium works, such as The Sword-holding Great Devil Vidyaraja (Plate 4) and Astro Bodhisattva (Plate 5) can be seen to exemplify how Yang Mao-Lin focusses on the symbolic framing of his dissenting vision in attempts to stretch cultural boundaries, and the works exhibited in Temple of Sublime Beauty: Made in Taiwan, which represented the Taiwan Pavilion in the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009 the summit of this creative endeavour. Invited by German curator Dott Felix Schoeber, Yang’s sculptures of Eastern hybrid deities (Plate 6), A Story About Affection – Extraordinary Love Vajradhara (Plate 7), A Story About Affection – Beloved Mermaid Vajradhara (Plate 8) and A Story About Affection – Beloved King Kong Vajradhara (Plate 9), invaded the Saint Giovanni e Paolo Church, the oldest and holiest Catholic church in the city, with their noisy manifestations of religious-cultural hybridity.

Plate 4

Plate 5

Plate 6

Plate 7

Plate 8

Plate 9

Surprisingly, dismissive reactions of the religious establishment against this curatorial arrangement and subsequent confrontation between art and religious faith, East and West, sacred and profane, did not happen as it had been expected. According to curator Dott Felix Schoeber, the local Catholic clergy simply regarded Yang's sculptures of Mazinger Z or Peter Pan as interesting works of art which would pose no threats whatsoever to their faith in God: “What Jesus Christ has been through was far worse than simple expressions of dissent. He was crucified on the cross; a few wooden statues will not make him fall off the cross again.”

It was, ironically, the servants of the secular public administration who cried desecration when presented with the curatorial proposal of Yang Mao-Lin's exhibition. The Venice municipal agency in charge of preserving cultural heritage reacted with disapproval, stating categorically that the achievement and cultural-historical status of the Renaissance is beyond the reach of any living artist. It was therefore decided that there would be no mimicry of any statues near Scuola Grande di San Marco or any of the marble statues of the saints on top of the church roof of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. It seems that instead of breaking down a whole system of signifiers and codes, Yang Mao-Lin's latest works, by putting together various different kinds of realities, simply softened the rigidity of the system as they infiltrate the subconscious of the public and alter its ideological contents. Such an artistic tactic may appear subtler, but by no means is it any less effective or less fascinating than attacking the system from the outside.

Inception: the Inward Ecstasy of Expanded Consciousness

As discussed in previous paragraphs, Yang Mao-Lin's artistic style has undergone a major shift in the last decade from a confrontational to a more cunning, debilitating approach. This change calls for comparison with the Hollywood blockbuster movie Inception (2010), in which the main character Dom Cobb enters, and plants life-changing ideas in, the dreams of his targets as he also tries to heal his own mental wound. The act of infiltrating one's dream may be a gentle one; the subversive power lies in the idea itself. As Cobb in Inception puts it, “An idea in your subconscious can rewrite all your rules of living.”

On the other hand, however, while on of the most captivating object seen in the film Inception is a spinning top which Cobb uses to distinguish between reality and dream, Yang Mao-Lin does not appear to offer a marker of boundaries of this sort in his works. As far as the artworks are concerned, if there is such a thing which marks the inside from the outside, or dream from the reality, it would probably be the “white cute” i.e. the mechanism of art exhibitions. Once inside of the white cute, one can just do as one wishes.

Sometimes it is hard to reach a satisfactory conclusion as to what has driven an artist to change his direction – social-cultural factors, inner impulse, or personal growth. In the case of Yang Mao-Lin, all that we know is that he has, in the past, confronted and challenged the institutional system of power with strong-impacting images, but is now choosing to shift the boundaries of reality through creative visualization which promises an ecstasy of expanded consciousness.

Perhaps one can ask this question: does a slippery consciousness not stand as the dualistic opposite of the hard, solid, homogenous stance of subjectivity? If that is indeed that case, it can be suggested that Yang Mao-Lin's “melting pot” serves as artistic representations of liquid subjectivity which, habitually associated with the qualities of fluidity and mobility, pass around solid obstacles and dissolve the solid mass with lightness.

Yang Mao-Lin's works have indeed accommodated different cultural and symbolic systems: the East and the West, the sacred and the profane, art and religion, the local and the global. More importantly, Yang's “melting pot” of these cultural-symbolic systems, which effectively erode the rigid boundaries which have once shaped our understanding of the universe, can be seen to illustrate the spirit of “liquid modernity” – a term which sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has coined to describe the present condition of the world as contrasted with the "solid" modernity that preceded it. According to Bauman, the passage from "solid" to "liquid" modernity has created a new and unprecedented setting for individual life pursuits, confronting individuals with a series of challenges never before encountered. Social forms and institutions no longer have enough time to solidify. In our time of liquid modernity marked by a redistribution and reallocation of modernity's 'melting powers', “interpreters and brokers [are] taking over most of the task previously reserved to the legislators”,1 and “life-politics” takes over public politics, critical theorists are having to adjust their role to become interpreters between different systems of perception in a bid to assist and promote autonomous communication between cooperating agents.

As Bauman describes, “From the meeting with solids they [liquids] emerge unscathed, while the solids they have met, if they stay solid, are changed – get moist or drenched.”2 Bauman's conceptualization of “liquid modernity” leads one to contemplate if the attacking force, the the clenched fist which was once aimed at the solid rock of political authority, will remain a rock solid, homogenous entity after all.

One may go on to ask further questions: is the solid still existent? If it is, then in what form does it exist in our current society? How does Yang Mao-Lin return to reality, once he has initiated into a full-blown fantasy and entered a different realm of reality?

For modern subjectivities, to evolve from solids to liquids is to strategically avoid direct confrontation and overt conflict with the rigidity of the inflexible, collectively-oriented order. It also allows for sufficient fluidity and dispersibility to infiltrate across the furrow boundaries of the system to plague it with endless waves of ecstasy. To conclude, I would like to quote Cobb from Inception again to help understand the fluid and mobile nature of “liquid subjectivity”: “You never remember the beginning of your dreams, do you? You just turn up in the middle of what's going on.”

全面啟動之後

郭昭蘭

作為台灣解嚴以來第一代藝術家,悍圖社成員楊茂林的藝術歷程與這個島上所經歷的一切,已經提供足夠的時間寬幅,讓人重新去想像這條綿密而轉折的軌跡;個體如何對應於更大的集體,是把自己平行的置入作為推進力量,抑或是轉身向更為個人想像的浸潤,以腫脹的精神意識迴避所謂集體迫切的危機?或者,那個被拿來對應於自我的集體,從社會政治轉向了文化商品角色的投射。後者顯得避世,但是否實則進入某種更加難以捉摸的社會情境?

1980年代,楊茂林的「真理」(圖一),「肢體記號篇」等作品將他推向台灣當代藝術的舞台;飽滿的拳頭,向著觀眾的方向出擊。「Made in Taiwan」系列並置歷史性符號, 向著集體的主體意識發出他的言論;而那同時也是台灣社會所謂主體意識討論最為迸發的時期。那隻出擊的拳頭,令人聯想到墨西哥海報(圖一),1968年的新左派停止徵兵運動(Stop Draft week)(圖二),以及許多學生運動,女性運動的圖騰。激進的抗爭是他們共同的態度,立場鮮明,態度堅定。

圖一

圖二

圖三

就這樣楊茂林與他同時代的藝術家,建立了台灣藝術史屬於當代的最初始軌跡與實踐,他們對台灣性(Taiwanese)本身的主觀關注,呼應了解嚴後台灣社會集體熱切的情緒; 終於,在長久的遙想他鄉之後,藝術的語彙向著這個島上發出了他們的聲音;作為藝術家必要的使命感,建立了他們與這個逐漸開展的藝術史之間的初始關係。隨著藝術體制的逐漸建立,屬於市場機制與美術館機構的力量與他們背靠著背地,相互支持構建這個島上逐漸成型的藝術歷程。

站在拳頭對立面的那個東西如果是硬版一塊,藝術家的身軀則相對單薄,但也因此確立了藝術家相對陽剛而英雄化的姿態:對於迎面而來的龐大集體,用拳頭去對應。從作品處理的意識來說,經歷解嚴世代對現實衝撞與對抗的姿態,楊茂林在世紀末進入21世紀之後的系列如「持劍的大魔明王」(圖四),「原子小菩薩 」(圖五),中被框架出來的界限則比較像是符號文化平台上的,他像是投身想像幻境的肉身,硬漢拳頭被一個越來越膨脹的滑溜精神體所取代,輕快矯健地在他的意識幻境中滑行,彈跳,跨欄,飛衝 ,彷彿對立的姿態被拉高成純然感性的張力。只怕不夠噴張,張力不夠飽滿,不夠腫脹。於是藝術家身段更為柔軟,也更為狡猾的戳揉於文化上可能的疆界。我認為這高潮正是2009年威尼斯雙年展中的「婆娑之廟─ 台灣製造」。矗立在威尼斯最古老教堂SS Giovanni e Paolo的「東方神起」(圖六)。「無敵愛金剛」(圖七)中無敵鐵金剛與女金剛為所欲為的合體 ,變種的動漫角色「人魚愛金剛」(圖八),「金剛愛金剛」(圖九)等頭上發出了神像該有的光環之後,一一登上了莊嚴的天主教的聖殿。

圖四

圖五

圖六

圖七

圖八

圖九

在聰明的策展人巧妙的安排之下,這些「東方神起」進入了西方天主教的聖殿,開始想像中應該要發生拳頭般的對峙。然而,根據策展人的敘述,這想像中保守教會的反彈事實上並沒有發生,因為「對當地的修女、僧侶和教士來說,楊茂林版本的無敵鐵金剛和彼得潘只不過就是非常有趣的藝術作品:安其羅神父的回應是,區區的木製雕像並不足以動搖堅定的宗教信仰,他說『耶穌什麼大風大浪沒見過,不會因為這種小事就從十字架上跌下來。』反倒是世俗市府,「當我把楊茂林計畫書的原稿程交給威尼斯歷史遺產行政單位時,大喊“褻瀆神聖”的並不是教會,而是世俗政府:他們的反應是,義大利文藝復興是神聖的。一個還活著的藝術家搆不上如此崇高的地位,更不得凌駕其上;因此,不准有雕像模仿附近聖馬可會堂(S. Marco)和歌德式的聖約翰與聖保羅教堂(SS. Giovanni e Paolo)屋頂尖塔上的大理石聖像」似乎,圍繞在楊茂林作品周圍的,重點與其說是它解開了什麼象徵系統,還不是說是怎樣膨脹的精神意識滑溜地搓揉了堅硬的系統,將現實以怎樣的姿態加以合併。所以讓作品外引的系統的搖撼與它內部象徵系統的摧毀,同樣迷人。

腫脹的精神 意識的狂喜 全面啓動

從硬漢意識到柔軟滑溜的精神體,與作品並進的作者意識在此顯得如此的不同。 這讓我想到2010年好萊塢電影「全面啓動」(Inception)中主角柯柏如何藉著侵入他人的夢境,植入足以改變現實的意念,進而處理自身的精神創傷。侵入夢境看似一個無須動武揮拳的溫和行動,但有趣之處就在於心靈想像的本身,只要你敢想,要多囂張就有多囂張,要多顛覆就有多顛覆。就像電影裡所說的「一個單純的意念可以改變世界, 並重寫所有的規則。 」但是「全面啓動」中有一顆旋轉的陀螺,總是用來作為提示區別現實與幻境的索引; 只是,在楊茂林作品內部,並不存在這樣的旋轉陀螺。如果有的話,那就是作品外部那個白色方塊(white cube)所指射的藝術機制。進入這個白色方盒子,你可以隨心所欲。

有時我們難以追問藝術家姿態的轉變究竟來自外在社會的,個人內在衝動的,抑或是創作生命的開展,總總分析總是無法串聯出一條令人滿意的說法。但我們知到這是一位曾經對應現實,如今卻選擇在作品中自現實轉身,以深入幻象之境,膨脹其幻想狀態的藝術家。我們知道,在這裡我們即將經歷意識全面的登鋒狂喜,一個被藝術家全面啓動的「優雅的精神惡搞行動」。

或許可以這樣問的是,是什麼東西站在滑溜精神體的對面。是否正是那像拳頭一樣堅硬的主體意識。一個被想像成無可分裂而完整而堅固的主體意識。那麼從楊茂林的優雅的精神惡搞行動中我們經歷的就是如液體一般流動,消毀沿途堅固一切的液化了的主體,流動輕盈而具延展性的主體。

在作品的表面,楊茂林捲入了各種差異的象徵系統: 東西方動漫系統的與宗教意識的、世俗的與宗教的、美術殿堂與宗教殿堂的、在地宗教與全球文化商品的種種疆界;在此同時,他在作品的後面同時演繹了液化主體之樣態,這正好與包曼(Zygmunt Bauman)所說的液化的現代性有著互相說明的意味。包曼認為生產機制與權利運作方式的轉變,使得固態現代性中那種由以立法者之姿態發言的知識份子,在全球化的時代正被詮釋者這種角色所取代。他們是周遊於各種系統的詮釋者,協助轉譯,促進自主性的參與溝通。

包曼曾經比喻當固態遇上了液態的時候,液態不會受損,而固體卻容易遭受溶解、侵蝕、甚至滲透。如果這樣的對照是可行的話,我們能否從這裡回望當初當初拳頭指向的方向,是否仍然鐵板一塊呢?

鐵板還在嗎?鐵板現在又以怎樣的方式存在呢?楊茂林的幻境全面啓動之後,是以怎樣微妙的形式回到現實? 最後我想用「全面啓動」電影中的一句話,「我們不必知道夢是怎樣開始的,我們總是從中間進入 !」來說明這種液態主體意識的機動流質性。也許是為了順應更加難以捉摸的現實系統,個體化身為更具彈性的流質器官,以保障自身免於在硬碰硬的層層關卡中,粉身或碎骨。液態同時保證提供足夠的擴散張力,去滲透進入每一個堅固的系統,飽滿而囂張的將他的狂喜覆蓋在無所不在的堅固殘餘。

全站熱搜

留言列表

留言列表